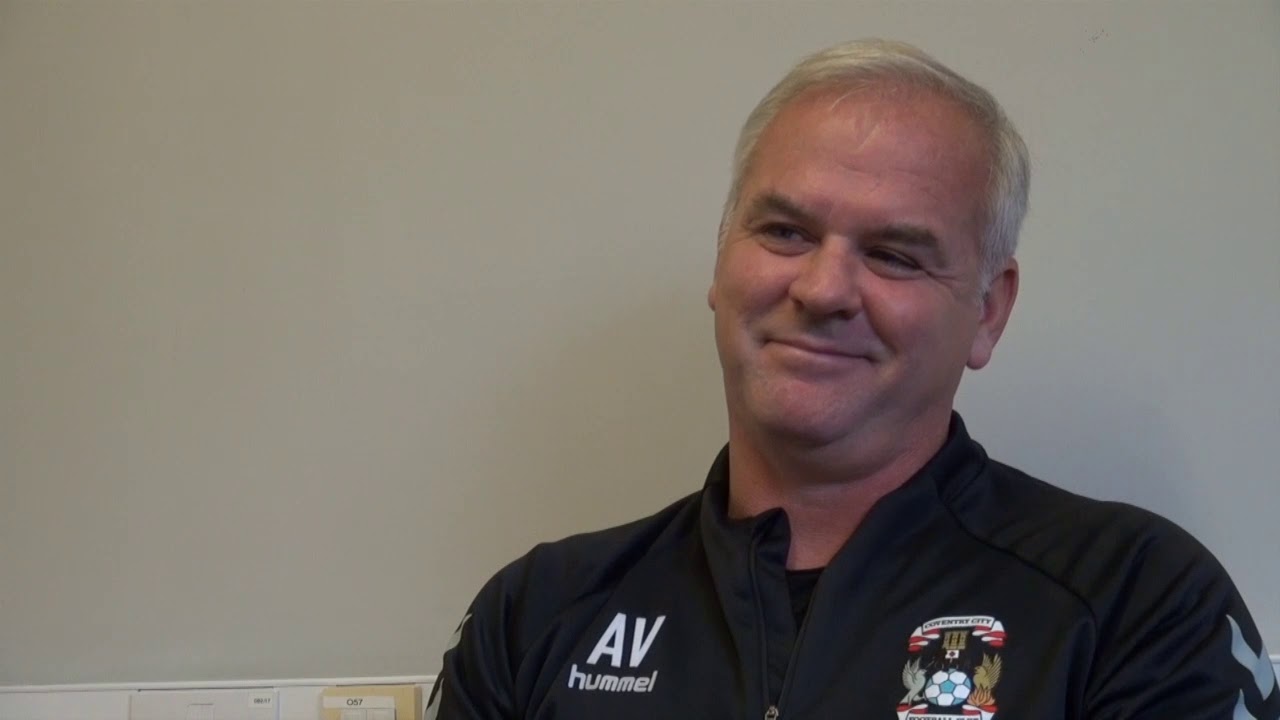

Coaching philosophy, nearly getting the sack, personal tragedy & working at Woolies – Adi Viveash exclusive

Part one of exclusive interview with Coventry City assistant manager and head coach Adi Viveash as Mark Robins’ right-hand man lifts the lid on his time with the Sky Blues

Adi Viveash is, without doubt, an integral part of Coventry City’s success under Mark Robins – the club’s assistant manager and head coach; the man who ‘paints the pictures’ on the training pitch, according to the Sky Blues boss.

He can also be ‘difficult,’ by which Robins means he’s far from being a ‘yes’ man, which makes them a perfect partnership that has masterminded the club’s rise from League Two to the brink of the Premier League.

But what about the man behind the gruff exterior, the human side of City’s tough task master on the training pitch? Here, the highly decorated former Chelsea youth and development coach who won everything going at Stamford Bridge, opens up about his early days, a hard, working class upbringing and the personal tragedy in his life that helped shape the man he is today – a father figure to so many players as well as a brilliant coach.

Sky Blues reporter Andy Turner sat down with the 54-year-old to find out a little bit more about his journey in football as well as in life, from his playing days to coaching elite Premier League prospects, and back down to lower league seniors at Coventry. He lifts the lid on what goes on in the dressing room, the stories behind some of the biggest games in the rise up the football league to the Championship, including the incredible play-off second leg victory at Notts County, nearly getting the sack and his special connection with the fans.

In the first of three features – in the other two he discusses tactics, formations, the evolution of individual players and the team as a whole, his relationship with the ‘gaffer’ and finding love – I started by asking him how he went from a seemingly rugged centre-half and master of the dark arts largely in the lower leagues to an educator of the beautiful game.

“I was a bit of both, to be fair. I knew the dark arts but I could also play, and I was fortunate to have some good managers,” he said,

“When I was at Swindon I had Ossie Ardiles and Glenn Hoddle [as manager], so my philosophy on coaching was honed at a young age. I was only 20 when Glenn was there when Swindon got into the Premier League and he was player/manager and I was back-up for him, so when he didn’t play, I did in the centre of a back three. And so from there I could see the centre-backs in a three working the width of the pitch, which was quite early in my education.

“But I was signed for my home town Swindon as a striker, scored a lot of goals in my schoolboy years and then for some reason someone upstairs took away the pace I had when I was young and it was Ossie who said to me, ‘You can see the game well,’ so suggested I play at the back. We had a giggle about it and then I played there in a pre-season friendly in Ireland against Everton. Norman Whiteside, Tony Cottee and Mike Newell were their strikers and we lost 2-0, but I played pretty well next to Colin Calderwood, who obviously went on to play for Spurs.”

He added: “I left Swindon when Steve McMahon was manager and went to Walsall. It was the time when you signed a contract but they could give you two weeks’ notice and you could give it to them. I could have gone to five places in the summer but the club blocked it and in the end it was November. My eldest son, who will be 30 this year, had just been born and he (McMahon) called me in one day and said they were letting me go, that it was a financial thing.

“I was in a little bit of a mess, and actually thought I was going to go and do a football in the community role at Yeovil and play at Huish Park, but then Chris Nicholl, who we have lost recently, god bless him, asked me to come up to Walsall.”

Viveash met Chris Marsh, who became a Walsall legend and is now Coventry’s kit man, and also had a season playing with Robins.

“Marshy was playing and I marked Kyle Lightbourne, who went to Cov, and I signed for a month. That turned into the end of the season and I ended up having five and a half years of probably the most enjoyable time of my career. We got promotion to the Championship – an incredible achievement to keep Man City in the play-offs and finish second behind Kevin Keegan’s Fulham.

“Chris (Nicholl) really improved my defensive side because I was a ball playing centre-half, used to like left to right switches. The gaffer (Mark Robins) came that year when Ray Graydon was in charge, so I was fortunate to work under the calibre of managers I did.”

He added: “Lou Macari was my first manager at Swindon in League Two; bang, bang, all physical running. We used to do six-mile runs on a Thursday and they finished with 100-odd points and just used to run all over teams, but it was interesting to see how he managed, and you take different things from everyone.

“I finished at Cirencester in the Southern Premier League at 37 after 20 years, playing for a bit of fun rather than playing to pay your mortgage or the bills. It was nice to go full circle and play with lads who were coming in after a 12-hour shift working at Honda. I had so much admiration for non-league players after I’d been there.”

Viveash dropped out of football for a short while, working in a factory and even at his local Woolies.

“I did normal jobs after that,” he revealed. “I’m from a little place called Wootton Bassett. Well, it’s Royal now, a little town in Wiltshire. My mum and dad worked really hard. My dad was an engineer and he would come in from work and then mum would go out and work nights, so we didn’t have a lot of money, never went on a foreign holiday. But they provided for us and my dad was a proper man.

“And that’s probably why I can resonate with the Coventry fans because there are a lot of people who have difficult times but they come and really support their team. I think I really understand that, coming from quite a difficult upbringing, in the sense of everything was a fight. I had to fight in my career as a player and as a coach to get where I wanted to be.

Woolies

“I did normal jobs, worked at Honda on a press for three months with a lovely big Polish fella who knew I wasn’t very good at it but taught me. I was a normal bloke, who did normal things to put food on the table.

“I worked at Woolworths packing up orders, sweets and things, used to go there at 5.30 in the morning until 1.30 in the afternoon and earned very little wages but it was just the discipline of carrying on and getting through that period. As a chocoholic, it was all right.”

Opening up to reveal the personal tragedy in his life, he added: “A lot has gone on in my life. I have had difficult things. My second son Toby, who was 23 last week, was a twin but his brother died and that happened while I was playing for Reading.

“We got to the play-off final and actually lost to Walsall, after I’d left the year before. My dad waited until after the game and told me he had cancer and that he didn’t want any treatment, so three months later he was gone.

“Then Toby was in hospital for the first year of his life, fighting for his life with five life-saving operations because he was born with long gap esophageal atresia. Basically his stomach had to be stretched up into his neck after being born three months premature, the weight of a bag of sugar.

“So there was a lot that went on, a period of time that really shaped me. I found it really difficult, I’ll be honest with you. It was a tough period in my life but football really helped me because it was the only time I could switch off; when I played.

“The next year we went up with Reading with Alan Pardew, finishing second. It was a difficult period but it shaped me and when I started coaching I was able to help players, and that was quite a nice loop to be able to look at it in a different way, which I certainly do now.”

“We were 2-1 down in that game, a local derby with West Brom, and no-one was catching him. He was running straight by me, so why wouldn’t I? I never hammered him down. My hand was behind his back and I broke his fall. He never even touched the ground because I held him underneath with my arm, and as he got up he looked at me as if to say, ‘you broke my fall there,’ so he was in no danger whatsoever. But I have this persona that I am some sort of lunatic.”

Lunatic

He added: “I have a very, not soft, but very caring side that I generally only share with the closest people to me and my family and friends. And when I work with players. Since I have been at Cov in the last six and a half/seven years there have been many occasions where players have come to me on a personal level who have been going through some difficult stuff. And they don’t know my story.

“The Chelsea boys know it because I told them, and I shocked them. When they were reaching out I tried to say to them that they are not alone, this is what happened to me. There was some other stuff that happened to me that I would never, ever make public but some of them know it because I told them because at that moment in time they were breaking. They needed to be shocked a bit to get them out of their own situation, knowing that they are not alone and thinking, ‘if Adi can get through that then he can help me with this.’

“It’s carried on here because around the training ground and after a session has finished you might see the gaffer on one side talking to a player, Dennis (Lawrence) would be talking to someone else, Aled (Williams) another and me someone else, and not always about football. And that’s a normal, everyday thing. Sometimes they seek you out because they need your help away from the game. And I am equally proud of the work we have done here as much as we have helped shape certain individuals that maybe needed that to go to that next level.”

Some of his proudest work, however, is player development, seeing young talent grow and fulfil their potential, and there have been numerous examples at City during his time.

“That, as a coach, should be your proudest moment; when you see people develop. Callum Doyle is an example for me who, while he wasn’t our player, when he played against Bristol City at Burton in his first game, he got destroyed by Andreas Weimann and you think, ‘he’s got a lot to do.’ And now you see him playing left-back for Leicester and see what he’s done in the space of a year, so that’s credit to him, first and foremost, but also credit to the players and staff who worked with him here. So that’s how I get my buzz, if you like.”

He added: “Callum O’Hare’s journey from being a free transfer is another. He was obviously a good player but had only really played League Two at Carlisle on loan. Sam McCallum is another… There are so many. Duckens Nazon’s journey in League Two; people of all levels.”

Going back to the start of Viveash’s Coventry story, he’d spent a decade rising up the age groups and coaching ladder in youth football at Chelsea, partly through Jose Mourinho’s time at the club. He left his role of development manager in May 2017 and was in no rush to get back into the game. But a bleed on the brain meant that Robins’ number two, Steve Taylor, required time off and Adi got a call from his old team-mate to come and help out after the club had just been relegated to League Two, ‘a million miles’ from coaching some of the best young players in the world. Inevitably, it was a bit of a culture shock and an opportunity he very nearly turned down.

“When Mark rang me it was to help out because Steve, bless him, had that really horrible health incident and I was only meant to be here for three weeks,” he recalled, leaning back and taking a slurp of coffee.